When it comes to economic development tools, every state typically uses the same types of programs to encourage economic investment. Tax incentives are the most common method, typically using some form of an abatement on either property taxes or business taxes. A second way in which economic growth is encouraged is to use some form of a tax capture mechanism. The use of Downtown Development Authorities (DDA) or other similar programs can help pay for public improvements in specified areas with the notion that the improvements will stimulate other economic activity in the area.

The theory of tax capture programs is that the governmental entity expends resources to provide an environment that encourages additional economic activity to take place within a defined area. In the case of downtown commercial areas, the focus is on creating aesthetically pleasing public areas to attract and accommodate shoppers. As economic activity escalates, property values increase and the authority then “captures” the increased tax revenues from the area to repay the cost of the public improvements.

While tax capture programs are used with great frequency across the country, the results that Michigan’s communities see from tax capture programs can be significantly different than their counterparts in other states

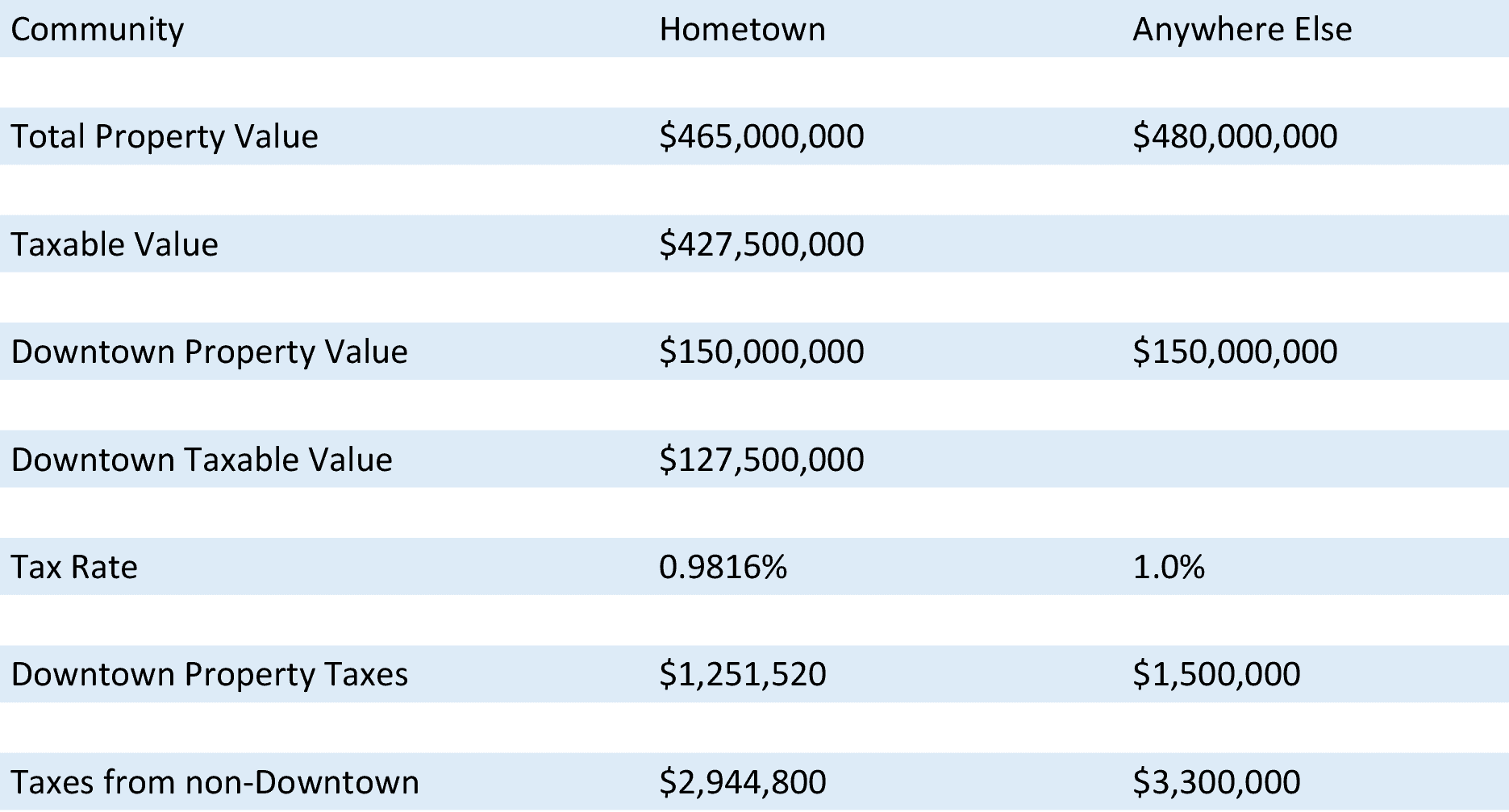

A hypothetical comparison of tax capture in Hometown, Michigan vs Anywhere Else, USA

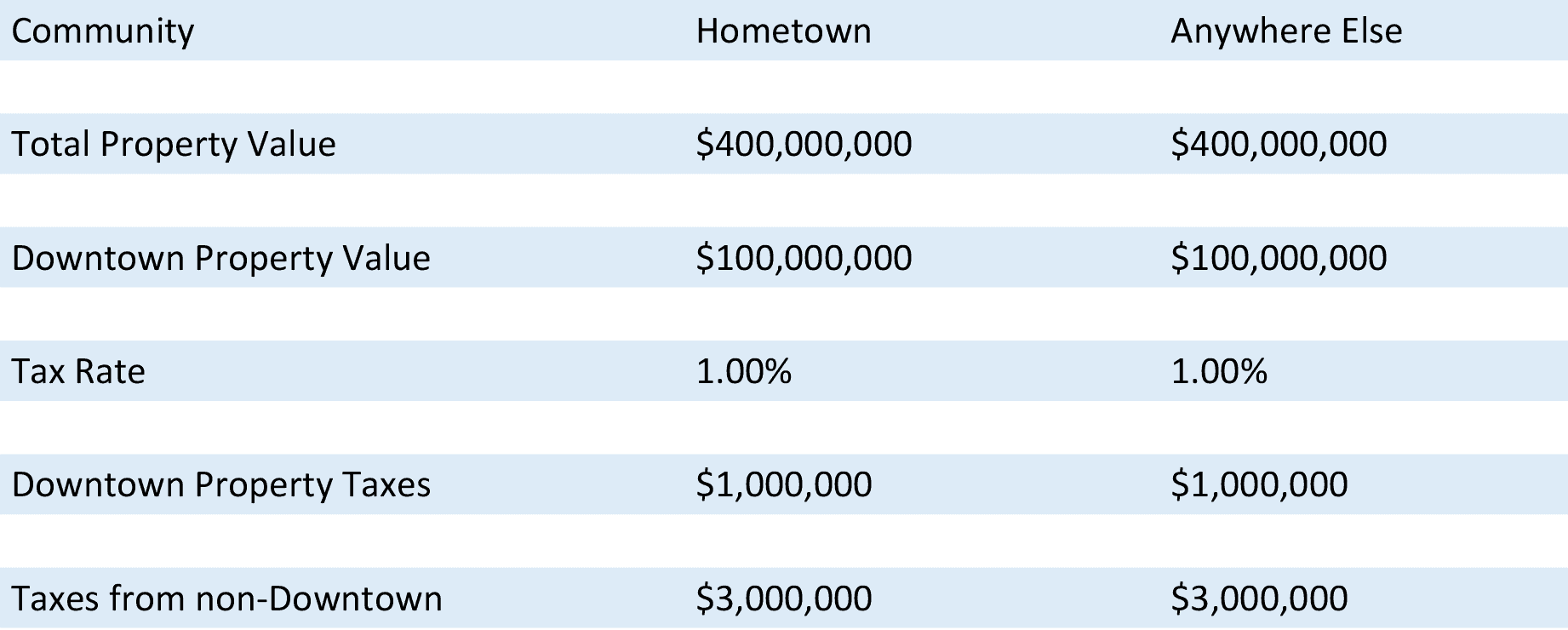

We can use a hypothetical comparison to look at the impacts, over time, of a Downtown Development Authority being established in two communities – one in Michigan and one from another state. For the sake of this exercise, we’ll call the communities “Hometown, MI” and “Anywhere Else, USA.” These are identical communities, where 25 percent of the property value is located in the downtown area and property is taxed at one percent of the property value. Inflation will be considered to be 0 percent during the time period of the study. Each year of the scenario laid out in this paper illustrates the various similarities and differences in Tax Increment Financing implications in Michigan as compared to other situations in the country.

Year One

Both communities invest $10,000,000 in the infrastructure of the downtown area with the goal of putting their communities “on the map.” As a result of the investment, numerous vacant store fronts are quickly filled, the downtown is bustling, and longtime store owners are seeing a major increase in business activity.

Both scenarios recognize that a thriving commercial enterprise requires an investment in the infrastructure. DDAs are designed to make public space conducive for private enterprise. In both scenarios, public investment induces a private economic response to create a thriving downtown area.

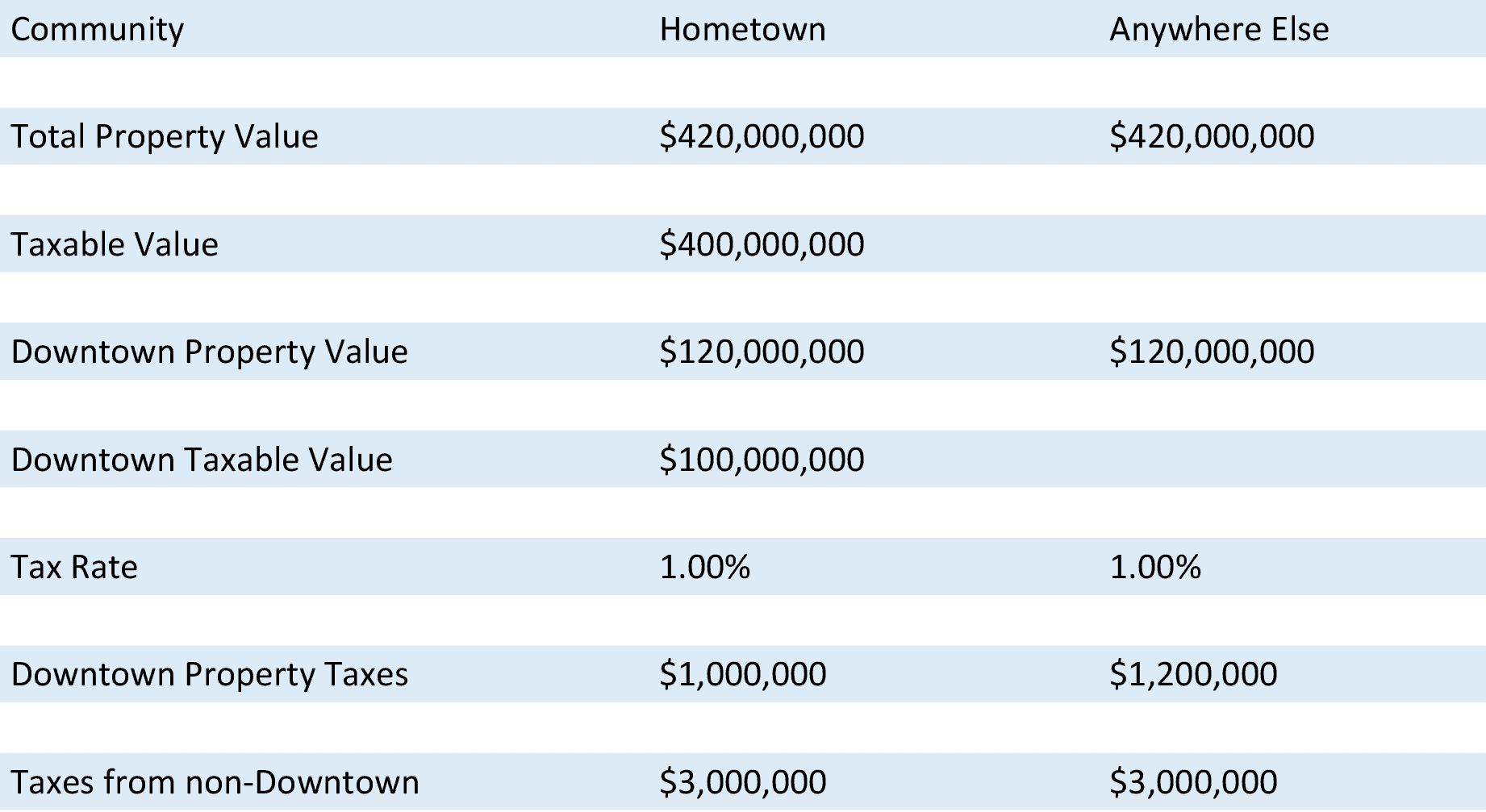

Year Two

In the second year, a resurgence spurred by each community’s investment in the district results in a property value increases of 20 percent.

The public investment has resulted in increased private property values based on the increased commercial activity. Sales are up, rents are up, property values are up, and the corresponding taxes follow suit; except in Michigan. The concept of public investment being the catalyst to additional private property values is the heart of tax capture plans. The increased economic activity is used to generate additional tax revenue to pay for the public investment.

Headlee, in conjunction with Proposal A, short circuits this very important component of the economic development strategy. While the enhanced economic activity will increase the value of the properties in Michigan, just like every other state, the increased values will not impact taxes. State Equalized Values will increase, but Taxable Values, the values used to calculate taxes, may only increase as much as inflation due to restrictions embedded in Michigan’s constitution by Proposal A, unless physical construction on the property takes place. This is a major limitation on the use of this economic development tool in Michigan compared to the rest of the country.

In this scenario, property values increased in both communities. With 0 percent inflation, none of the increased values result in increased taxable values in Michigan. As a result, there is no new revenue in Hometown, MI. Anywhere Else, USA uses the $200,000 in additional property tax revenues captured by the DDA to make the first payment on the improvement bond. Hometown must now look at making the bond payment from the city’s general operations budget, impacting services to the rest of the community.

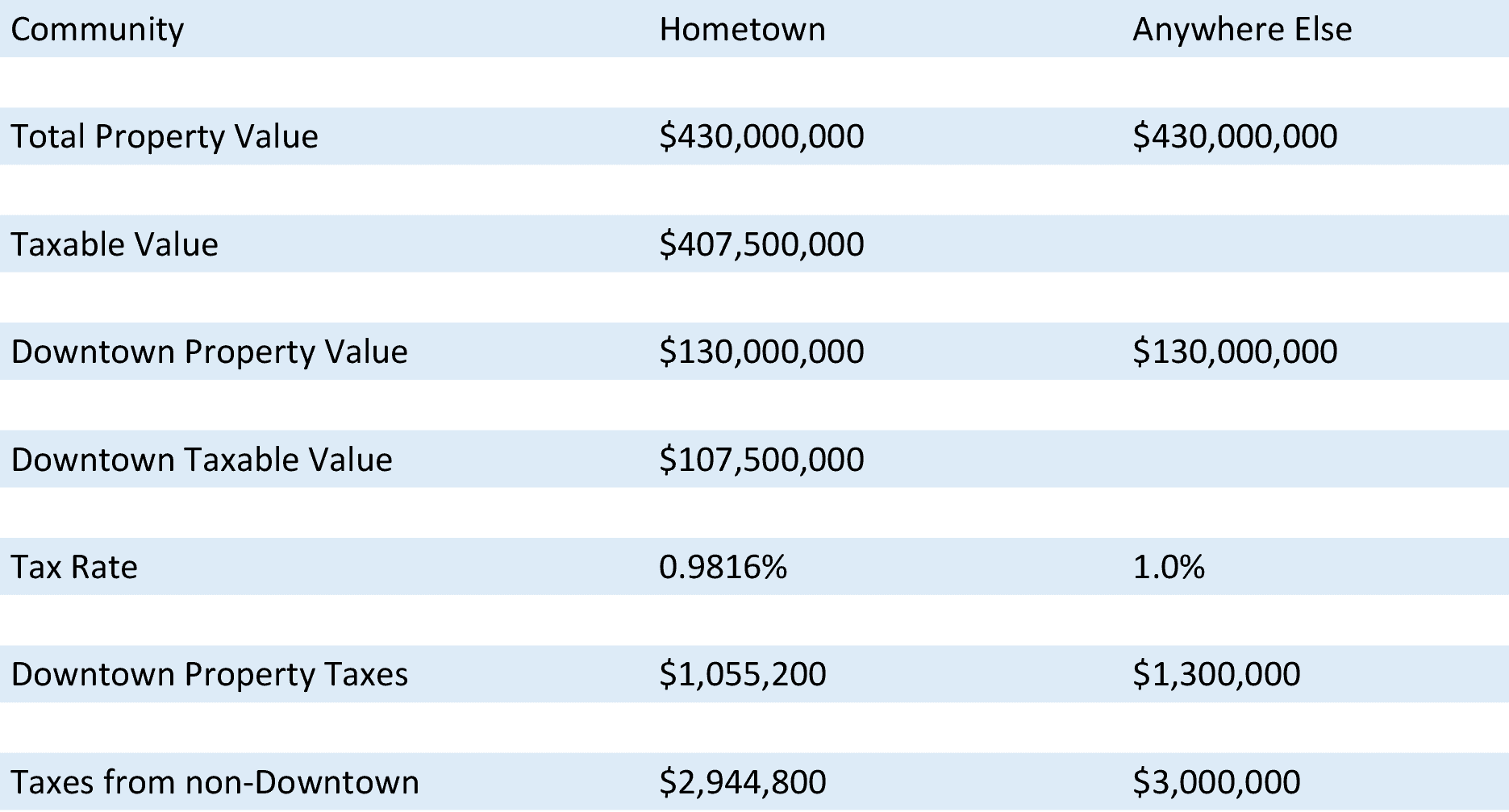

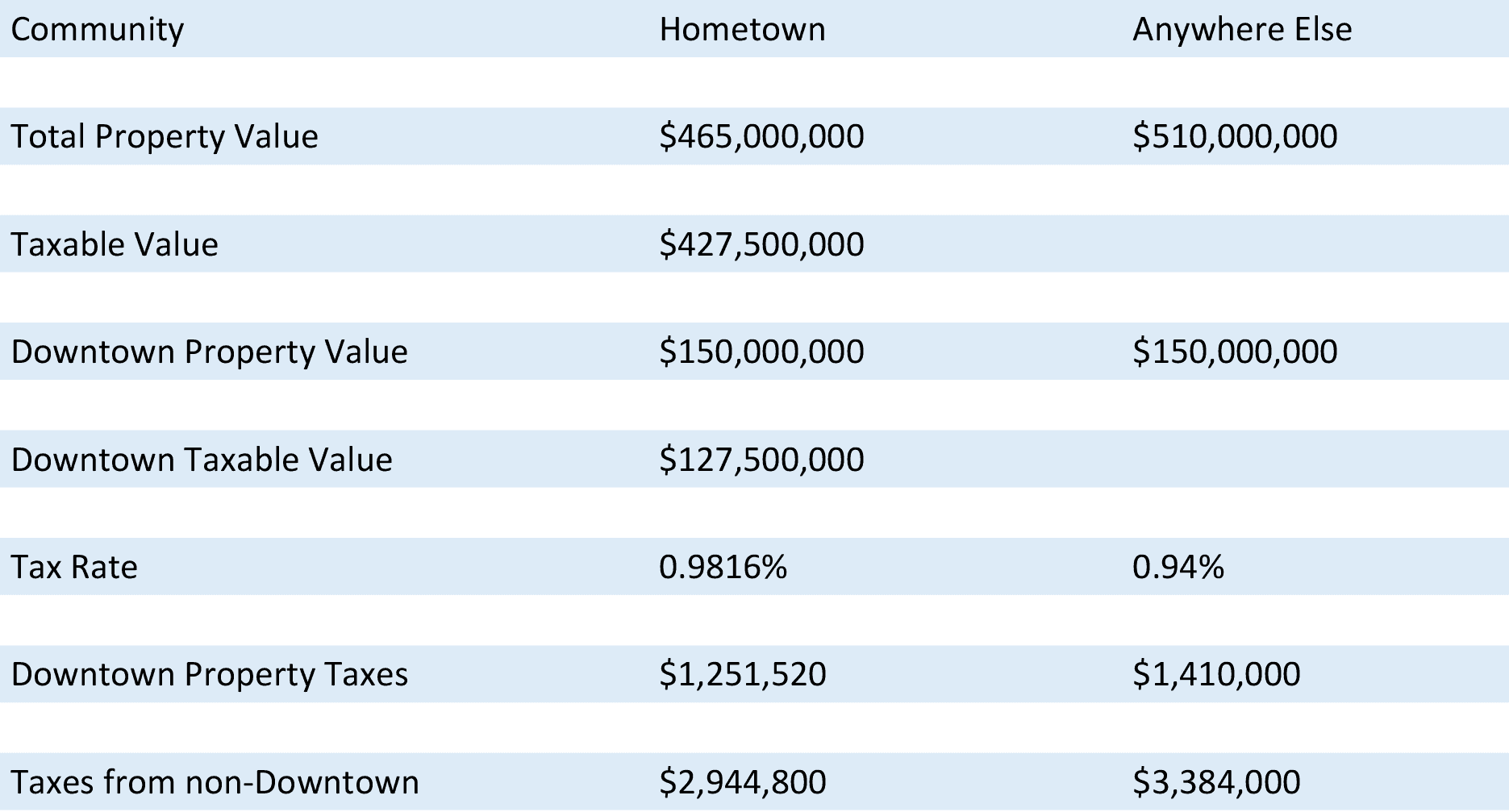

Year Three

The downtowns in both communities are now thriving, with 25 percent of the downtown property owners seeing a great opportunity to sell their property and let some new blood move into the downtown. Property values in the downtown jump again to $130,000,000.

Year three looks at the next evolution of the downtown. Excitement for a thriving commercial area brings prospective new property owners. Many property owners will retain their property, looking to ride the economic wave of revitalization, while others will look to profit and cash out by selling their property. This will likely bring in new dynamic property owners to the downtown.

In Michigan, property sales allow additional taxes to be collected as Taxable Values are uncapped on the properties that are sold. However, Michigan’s constitution once again comes into play. Headlee does not allow an increase in total tax collections within a community on existing property, beyond the rate of inflation. Zero percent inflation was used in this narrative to show the impacts of our constitution more clearly. In this scenario, the additional property taxes collected in the downtown area are not additions under property tax laws. As a result, the extra tax revenue generated from the new property owners within the DDA must be returned proportionately to all property owners within the overall community through a “Headlee rollback” in the city’s millage rate. Many property owners would consider this to be a very favorable policy, they end up paying less in taxes. In this particular case, while the total taxes collected in the city don’t increase, the amount that the city must distribute to the DDA increases. The DDA gains revenue from the tax capture, but the city budget actually losses revenues year over year because the DDA distribution is prioritized over the needs of the city. Again, in the rest of the nation, increasing revenues in the tax capture would not impact the rest of the city budget.

In our scenario, Anywhere Else is now using the $300,000 in tax capture to make full payments on the improvement bonds. Hometown, Michigan on the other hand has to deal with numerous calculations caused by Proposal A and Headlee. Property sales resulted in 25 percent of the downtown properties becoming uncapped, resulting in $7,500,000 in additional taxable value in the downtown and community overall. None of this value is based on additions, so the Headlee provision requires a rollback in the tax rate to 0.9816% of the taxable value. In total, the community is still only collecting a total of $4,000,000 in taxes, but $55,200 of those taxes must now be turned over to the DDA as tax capture. This causes a decrease in the general operational budget of Hometown. The DDA still does not have enough to pay for their bond, so again the Hometown must divert operational funds to make the bond payment. On the positive side, property owners across the city see a tax rate reduction of nearly 2 percent.

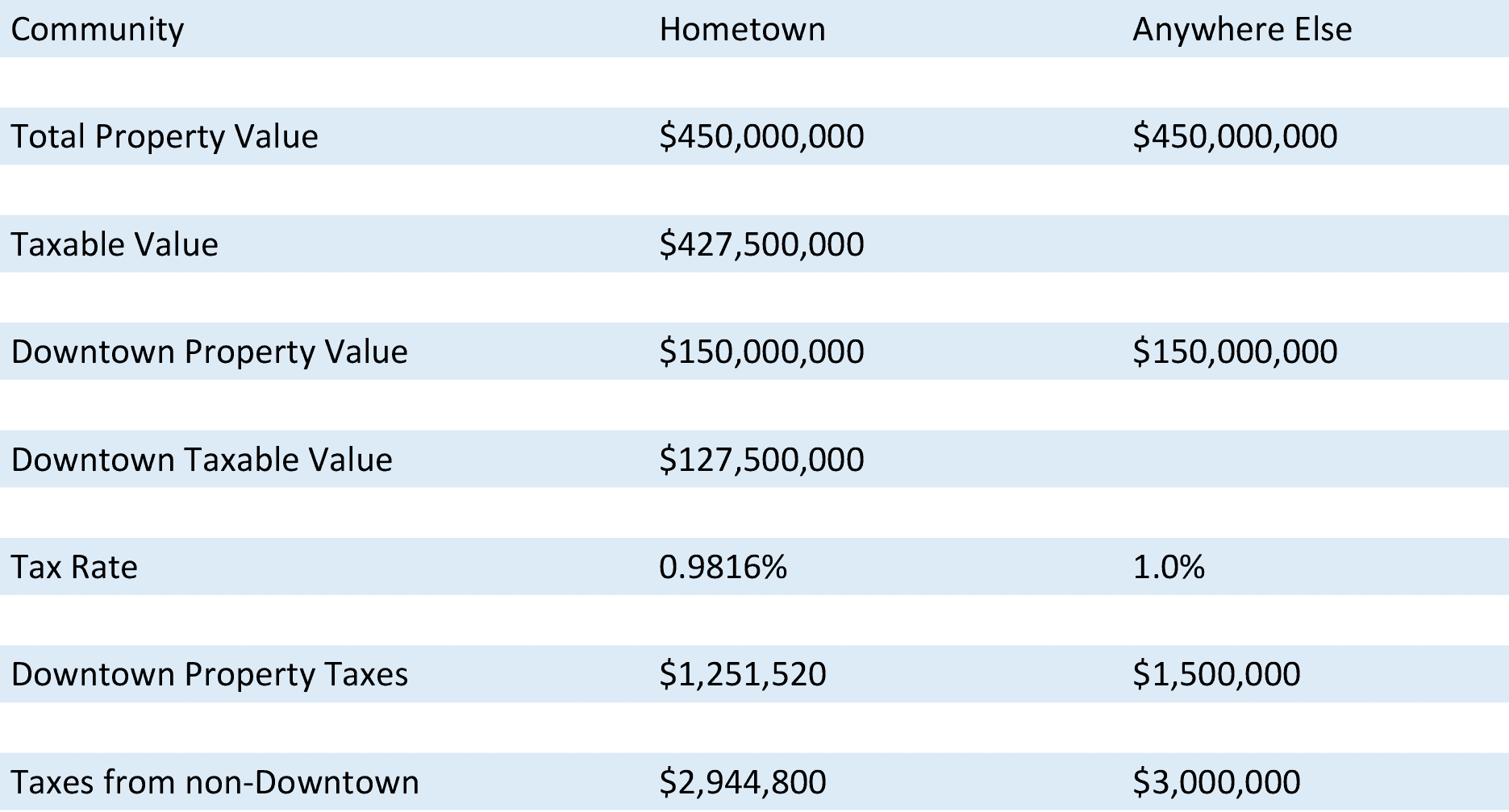

Year Four

This year, major buzz regarding the two downtowns pays off: $20 million in new construction from private investors takes place in each downtown.

Year four is the Holy Grail for economic development programs. Public investment creates a situation where new buildings are constructed. In this situation, the benefits accruing in Michigan are identical to what would happen in other states. Unfortunately, it is about the only time when Michigan’s tax capture programs to spur economic development actually create a positive result for local government revenues.

In our scenario, Hometown is allowed to retain all of the revenue associated with new construction in the downtown area. All of the revenue is transferred to the DDA, which is now able to pay for the bonds with their $251,520 in total tax capture. The city operational budget is still reduced below their first-year budget by over $55,000. On the other hand, in Anywhere Else, the DDA is now receiving $500,000. They decide to pay for the bond in the same amount as Hometown; setting aside $250,000. With the other $250,000 they implement a major program of festivals and events downtown.

Year Five

By now, property values for homes in both communities are increasing because of the thriving downtowns. Residential values in Hometown increase by 5 percent, while values in Anywhere Else increase by 10 percent due to the major activities now occurring in the downtown area.

Year five identifies the “priming the pump” problem In Michigan. In other states, the growth in revenues associated with the initial public investment increases revenues that can enhance the value of the initial investment, which in turn creates an even stronger economic driver; success breeds success. In Michigan, Headlee and Proposal A create stagnation after the original infusion of vitality. There is no compounding effect. In Michigan, it is one and done.

Year five spotlights the impacts of a thriving downtown on the rest of the community. Simply having a thriving downtown is not the end objective for tax capture programs like DDAs. The objective is to have the thriving downtown spur a resurgence in the overall community. Economic development departments are looking to create a thriving community, part of which is the thriving downtown. As described earlier, Michigan’s constitutional tax limitations short circuit many of the efforts that can be used to create a more attractive community. Communities across the state are working diligently to improve downtowns and neighborhoods, but Michigan’s property tax limitations effectively stop these efforts far short of what is seen in other states across the nation.

Once again, in other states the thriving downtown drives the appeal of the whole community and leads to additional revenue from the neighborhoods. This creates the win-win scenario that economic development departments seek: use public resources to improve one area, which leads to private investment in surrounding areas. This then creates additional revenues and extra energy to keep pushing revitalization forward. In Michigan, secondary impacts resulting in additional resources to keep revitalization efforts moving forward are significantly restricted. Stagnation is the more likely outcome than continued revitalization.

The scenario demonstrates that Hometown, MI is once again caught by the fact that property value growth associated with desirability does not translate into additional tax revenue. The city budget is still down by $55,000 due to the earlier Headlee rollback, but at least the DDA is paying for their bonds. Anywhere Else is now seeing the benefit of the ripple effect. They have an additional $300,000 per year for city operations, which is then used to provide improvements for the neighborhoods.

Year Six

Residents of Hometown, MI start to reinvest in their homes to match the efforts of the city to revitalize the downtown. Residents invest 5 percent in renovations to their homes. In Anywhere Else, property owners are more enthusiastic as their downtown has been revitalized and become activated with new events. In addition, new services to the neighborhoods are clearly recognized and residents respond with a 10 percent reinvestment in their homes.

Year six may demonstrate the biggest challenge that Michigan tax limitations create for the future prosperity for our communities. In Michigan, MCL 211.27 states that most renovation work done to existing homes is exempt from consideration when determining State Equalized Value. This would include new roofs, siding, electrical work, heating, drywalls, and other improvements. Once again, this puts Michigan at a significant disadvantage when compared to other states in the use of this and other economic development tools.

Across the nation, rehabilitation is the name of the game in revitalizing older communities. Rehabilitation and revitalization result in growing tax revenues for local governments, except in Michigan. The 1970s economy is ingrained in our constitution, which means that growth can only be measured by new construction. Economic growth needs to be measured by more than the construction of a new subdivision, which is what Dick Headlee observed outside his windows in the 1970s.

Because of MCL 211.27 and Headlee, assessors are not allowed to increase assessed values for renovations on homes unless they physically add to the structure with things such as new garages, decks, or other additions. In Anywhere Else, USA these improvements would likely increase the property values and tax revenues. In this case, the improvements would generate an additional $300,000 for the city’s operational budget. Anywhere Else could continue to reinvest more in their neighborhoods or they could use the extra $300,000 to reduce their tax rate by approximately 6 percent; they choose the latter.

Comparing the Outcomes of Hometown Michigan and Anywhere Else USA

In this fictitious scenario, both DDA efforts were successful in revitalizing the downtown. Economic activity blossomed and property values increased in the target areas. In other states, the associated increased property tax revenues could then be captured and used to pay for other public improvements and be further targeted to build on the initial success. In Michigan, if no new construction takes place, there are no additional property tax revenues. Any increased revenues that occur from taxable values “popping up” when a property is sold must be offset by a reduction in taxes collected on all other properties in the community under the requirements of the Headlee Amendment.

Michigan tax capture programs are beneficial to the businesses in the impacted area. The programs have the potential to increase employment, stimulate the housing market in the surrounding area, and generate additional tax revenue for the state as they help move the economy forward. But compared to other states, Michigan projects are likely to fall short of the benefits that accrue in other states and are far less likely to sustain and expand on their initial success. Other states generate far more additional local tax revenue to support the infrastructure and services under their tax capture plans. This lack of sustaining investment has put Michigan at a significant disadvantage compared to other states.

In 1978, we placed strict limitations on how local government revenues may grow. It was put into place to protect property owners from excessive taxation. While it has achieved this goal, it has also contributed significantly to economic stagnation in our state. Our fully developed communities have been especially hard hit by the concept that economic growth is only achieved by building something new, especially in an era where vitality is measured by how much you rehabilitate something you already have.

Headlee allows local government revenues to increase when growth occurs. The population of our state has increased by eight percent since the Headlee property tax limitations were put into place, while the rest of the nation grew by 48%. Growth has been a hard thing to come by over the past half century. As a result, many of our local governments – especially those in areas of the state that are fully developed – have been put on a fixed income. Unfortunately, this fixed income has been in place for nearly 50 years. Can Michigan withstand continuing down this same economic development path for another 50 years?

Leave a Reply